|

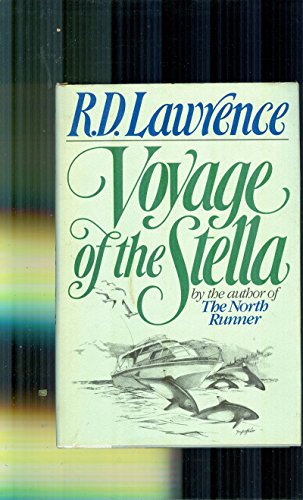

| The original hardcover |

Something a little less likely today--and after a gap in posting of nearly a year, alas...not a lot of time for reading for pleasure!

Like many an unrepetent devotee of the printed word, I frequently pick up books of a certain age from the bargain bins of those bookstores that persist in our increasingly reading-hostile world. At least, I consider it hostile to reading at length, and for what might be considered pleasure, and with a measure of comprehension.

I found such pleasure and comprehension in this volume, written by Canadian naturalist and wildlife author

R.D. Lawrence back in 1982. It describes events 10 years prior to publication, when, in the wake of his younger wife's untimely death, he sought middle-aged solace in a motorboat trip to what we now call

Haida Gwaii. Part therapy, part marine biology, and all wonder, Lawrence's tale of his journey north to the Alaska/B.C. border is both interesting on its own merits and is quite revealing of how our view of the natural world has changed profoundly in the last 40 years.

I am rather abashed to admit that I knew nearly nothing of R.D. Lawrence, the man, or the public figure. While clearly

a nature writer of some renown, one whose extensive list of titles continues to inspire current readers (he died in 2003 and was writing well into the 1990s), much as do the works of

Farley Mowat and the programs of

David Attenborough, two still-living rough contemporaries of R.D. Lawrence and his peers in popularizing the joys of the natural world through description..

Like Mowat and Attenborough, Lawrence was that now-extinct breed, the self-trained naturalist. Armed only with scientific insight, and absent academic qualifications (see Jane Goodall, although she eventually obtained degrees in her field, having more or less

created her field), keen observers such as Lawrence were, through their writings, the interpreters for city folk of the natural world before much more than staged TV "nature" shows and a previous generation's (

E.T. Seton, artists such as

The Group of Seven) love of the natural, as opposed to the artifice of man, were available. Lawrence himself was a battle-scarred veteran of World War II, and came to Canada post-war having been served a more than generous portion of carnage. I detected in some of his ideas and statements a touch of what would today be characterized as post-traumatic stress disorder, a term which most of the WWII vets I've known would snort at. Whatever Lawrence's ills were, however, the cure was always found in the Canadian wilderness.

It's the early 1970s. The

Stella Maris is a compact, 24-foot motorcruiser purchased by the author in order to do specimen collection up the coast of British Columbia. Lawrence, salving grief, is straightforward about his rationale for undertaking such a potential hazardous (the boat is small, the ocean big; distances are great and settlement sparse) journey. There's no sposoring institution, and no real sense that much more than Lawrence's curiosity is driving the voyage. At best, it could be considered a "working vacation", although it seems to the poetic Lawrence to be much more.

Lawrence's comments about the natural world reveal much about the time in which he writes. Killer whales or orcas, as they are now generally known, are considered vicious, well, killers of larger whales, commercial fish species and one gets from Lawrence the sense that his contemporaries view them as a sort of 25 foot sea rat.

Not to Lawrence. His encounters aboard and while diving with curious and biddable orcas persuades him that they are intelligent and social creatures, which may have been news at the time, but which today most schoolchildren seem to grasp. That and Lawrence's rather ornate writing style seem to date this book, but it's simply the style of a man who wishes to use all of his rhetorical skill to convey simple truths: Nature is not our dominion, but is that within which we live, a totality from which we divorce ourselves at peril.

Lawrence draws parallels between the natural and less-natural worlds in the variable state of the native communities that he encounters on his voyage. Some settlements are depressing and full of drunken or otherwise damaged natives (we know a great deal more today, of course, why that might have been the case). Others are "dry" and seem more self-sufficient; Lawrence finds these places not only more to his taste, but closer to his philosophy of working with, rather than presiding over, the natural world.

An interesting read about a beautiful part of the world,

Voyage of the Stella, despite featuring a stinkpotter, is of interest to any sailor who not only appreciates travel by boat, but realizes that a boat can be a great platform from which to observe the beauty of nature...minus humans.