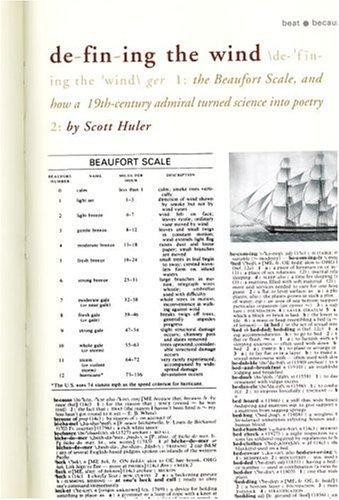

Defining the Wind: the Beaufort Scale, and How a 19th-Century Admiral Turned ScienceInto Poetry

by Scott Huler, Crown Publishers

ISBN: 1400048842, 2004

Even before I took up sailing, I was more

than vaguely aware of the time-tested and oft refined Beaufort Scale and its handy ability to

summarize the real-life effects of wind on sea and (later) land. What I didn’t

know was much about Beaufort, other than he was of Napoleonic Wars vintage and

was one of those polymath captains who turned to science after many years of

fighting for the British Navy.

Oh, and the Beaufort Sea in the Arctic?

That’s named for him, as well.

After reading Scott Huler’s somewhat

obsessive 2004-penned tale of how his own poetic, rather than his scientific, interest in the

Beaufort Scale drew him into a 200-year odyssey of research, sidetracking,

pilgrimages and mystery solving, I know more about a lot of things, one of

which is Scott Huler’s mental processes.

Huler was a copy editor when he stumbled

across Beaufort’s famous scale of wind effects in the early 1980s. There it

was, in a dictionary of all places, and he found the compact rhythm of “Force

5, Fresh Breeze, small trees in leaf begin to sway; crested wavelets form on

inland waters” a sort of nature-focused haiku, and he determined to learn more

about this Beaufort fellow and his windy prose. The result defines the wind, but perhaps not as he intended.

What he learned is that the story of

man’s measurement of the natural world around him has been a fairly slow and

torturous progression from “damn, it’s somewhat blowy out there, what?” to today, when satellites

can track rogue waves in the middle of empty oceans, down to the closest ten

centimetres, and no trip around the bay is complete with checking out Windguru. Beaufort himself (and while we learn a great deal about him, he is

only one of many characters in this story) was an exceptionally good, Cook- and Vancouver-level hydrographer

and surveyor, as well as a good observer of the natural world when he wasn’t

being shot in the face or the groin by the enemies of His Britannic Majesty.

Beaufort either devised independently or

modified an existing wind scale to sea conditions, and amended his original scale

in terms an average sailor would understand: thus, ‘Force 5, bring in topsails,

whitecaps form’, and so on. The scale didn’t achieve wide acceptance or the

Beaufort moniker until close to the end of Beaufort’s long and detail-oriented

existence; since then, it has seen derivatives such as the Petersen Sea State

Scale, and various land-based methods of clocking the wind by its effects on

one’s surroundings, not by its effects on those little hand-held windspeed

doohickeys increasing common in the Wednesday night club races.

No comments:

Post a Comment