Maphead: Charting the Wide, Weird World of Geography Wonks, by Ken Jennings

The author of this entertaining, breezy volume on "the secret shame" of cartophilia, or love of maps and charts, is perhaps best known as the most successful contestant on the perpetual TV quiz show Jeopardy. As might be expected, the book is as full of facts and asides and references as befits the writer's status as a polymath; what is less expected is that Jenning's writing is mildly witty, if firmly rooted in current cultural tropes.

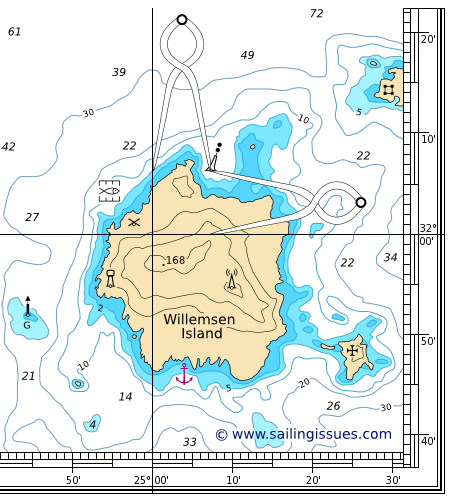

|

| Not for navigational purposes |

Jennings has in common with most sailors of my acquaintance both a fascination for and a facility with maps and charts of all kinds, along with the conviction that he is, or was, singular in his "geonerdiness". Geography as a school subject, which of course is much more than just map-gazing, is no longer taught to most children, a cultural decision Jennings, predictably, finds short-sighted. He returns at several points to our declining respect for "spatial intelligence", and our increasing reliance on navigation of the everyday world being outsourced to GPS-driven devices and smartphones. As a sailor, I hear (and occasionally see) the consequences of either failing to look beyond the screen in the boat, or failing to properly interpret what is being seen on either screen or before one's eyes. Navigation is a learned activities, and a map, either paper or electronic, is only ever an aid. In a world where maps of all types (find me a Thai restaurant, show me house prices in a one-kilometer circle) are downloadable to cellphone, the actual opportunity to orient oneself in space without assistive technologies are increasingly rare.

|

| Avoid sailing off the edge |

The one or two who read this may occasionally use a compass, the GPS-age equivalent of stone axe, and thereby learn to square headings and bearings with reality and the nearby presence of large iron objects. Others may have an innate sense of direction, or the knack of intuiting from cues in the environment their way around an otherwise unknown territory.

Jennings' book isn't about those people. Those people, salted with a sort of spatial OCD, are the start point for geonerds of landmass proportions.After a little personal show and tell and a brief history of cartography, Jennings delves into the various sub-classes of "mapheads": vintage map collectors, who spend millions on the products of centuries-dead cartographers, whose fanciful fillings in of the "there be dragons" sections of a poorly charted planet seem to spur some compulsive desire in the minds of collectors. It's not as if you can use a 16th-century map as, well, a map. Others map imaginary landscapes; Jennings notes that a key feature of most fantasy epics are lovingly detailed maps; J.R.R. Tolkien's "Middle Earth" and even the recent Game of Thrones series come to mind. Still others attempt to "bag", colonial-explorer-style, over 100 countries visited, itself a race against time as Jennings records that most members of the "Traveler's Century Club" are both moderately to very wealthy and moderately to very old.

Perhaps the most affecting and, as Jennings relates, personal chapter is related to a National Geographic "Geography Bee", for which children regurgitate astouding volumes of geographic factoids. Very much the poor relation to the better-known spelling bees, the Geography Bee is arguably more difficult and gruelling: Jennings, pop culture's Mr. Know-it-all, is humbled before the depth of these driven and sometimes slightly odd children and their vast geo-knowledge.

|

| Shouldn't this be an app? |

No comments:

Post a Comment